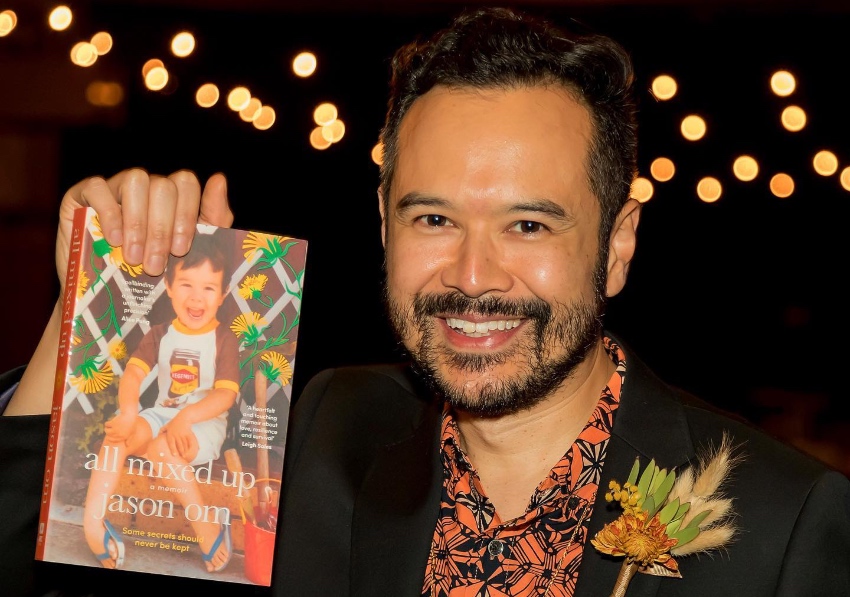

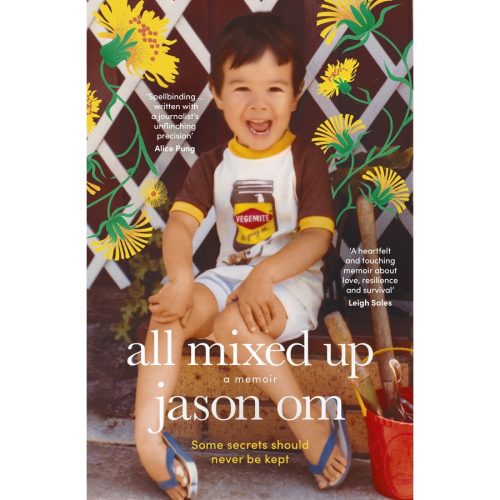

Excerpts From Jason Om’s Memoir: All Mixed Up

This is an extract from Jason Om’s memoir All Mixed Up, published by ABC Books and available now at all good bookstores and online.

Dad’s outpouring of feelings was a stunning revelation to me because I’d believed his tear ducts were non-functional.

Then I remembered the one time I’d seen a few sniffles. In 1996, Dad and I had travelled to Rome. At a rustic hotel, he tried to make a phone call at reception, but it wasn’t connecting and the Italian staff were indifferent to his plight. The woman in the little counter booth was speaking to an Italian guest as Dad retreated to a couch in the foyer. Incensed, he sat with one leg crossed over the other, muttering to himself.

‘Dad!’ I said, trying to rattle him out of his funk. He ignored me. I plonked myself on a chair opposite him, wearing a cap, an oversized T-shirt and baggy jeans. More angry mutterings escaped his mouth. ‘Dad!’ I tried again.

No response. What was wrong with him? Why is everything like this!?

‘Dad! We can’t just sit here in the hotel. How many times are we going to be in Rome? We only have two days, and we have to see the Vatican.’

When I looked back on this now, I realised he’d succumbed to his unacknowledged grief three years after Mum’s death. He was struggling to hold back tears.

Somehow I managed to get him off the couch and into the cobblestone street, where we jumped in a taxi. When we got to the Vatican, we discovered that the Sistine Chapel was closed for repairs, so we entered St Peter’s Basilica instead. ‘Wow,’ Dad said with his mouth open, teeth out, nose scrunched as he peered upwards at the spectacular domes.

I pulled out Dad’s work diary from 1993, which he’d given to me during my investigation into Mum. Flicking through the pages around that lonely time of her death, I found an entry that said Nan Ruby ‘rang to interrogate and scold me’. I then came across an entry that spoke of his private grief, something he’d never shared with me but had with a trusted colleague: Danielle is back. A talk with her about my sorrow.

Dad had taken little time off work. A fortnight after Mum had been admitted to hospital, he was back at his job. No one else could carry on his Khmer radio show. Back to normal, he wrote in his diary, dusting his hands.

I could see now how Dad had sequestered his feelings inside himself and spewed them out when he blew up, or hidden in his study when it all became too much to comprehend, during my teenage years when we clashed. I didn’t ask him what he’d been doing in his room all those times, but I suspected he’d been crying quietly, with no one to pat him on the back. If that were true, there was no chance in hell he’d ever admit it to anyone, let alone me.

This was why I’d needed to go digging through old documents to find the proof of his grief in that one line.

‘I read your diary,’ I said to him. I was standing at the kitchen bench while he sat at the table facing away from me. ‘That entry you wrote about your sorrow, that’s a lot to go through.’

He turned his head slightly. Then said nothing.

‘Dad, did you hear me? I said, that’s a lot to go through.’

Nothing.

*

Dad had once been much gentler towards me. Before Mum died, he used to call me kon, ‘son’ in Khmer. When I was very young, we hung out together in the old corrugated-iron garage that smelt of oily rags, WD-40 and rusting metal. I followed him around as he did his chores, and watched him dunk a dipstick into the engine of his Toyota Corona.‘Check the oil level,’ he explained.

Among the shelves of dripping paint tins, tools and assorted junk, there were a few plastic bags of goodies he’d saved from the potato chip factory where he and Mum worked. Inside were Cheezels and Burger Rings and Pac Man collector cards, which Dad handed out as treats.

We spent long nights spread out on the floral carpet of our small lounge room.

‘The cat sat on the mat,’ I repeated after filling in the blank spaces of my homework. ‘Is that right, Dad?’

He also gave me the answers to mathematical equations.

He helped me put oil into a toy steam-engine train on a circular track, and taught me how to play chess, though that was more like taking lessons in being beaten.

At night, Mum and I listened to the mwah-mwah-mwah of Dad’s voice speaking in Khmer, a language we didn’t understand. But it was Dad! On SBS Radio! We laughed along to the tinkling of the show’s theme, a melody in Khmer xylophone.

I used to hold Dad’s hand while at the shops in Oakleigh. His fingers felt like the soft sandpaper he kept in the garage.

But one day, I stopped. Something inside my head said I was too old for that, so I let go.

Then Dad stopped calling me kon.

Is that what happens to most fathers and sons? Is there a time when they shut each other off because showing emotions towards each other isn’t what it means to be a man? And does a father’s fondness for his son stop when that son falls short of his father’s ideal?

*

Back in 2013, photos of a friend’s grand civil union had appeared on my Facebook feed. Supremely fashionable, influencer-in-the-making Dean was getting hitched to his equally handsome Anglo-Australian boyfriend, Sam. Alongside pictures of them in matching navy tuxedos were shots of Dean’s Cambodian father and Filipino mother joining the celebration, the brightness of their smiles dialled up 150 per cent.

I knew Dean from my uni days, while our fathers had known each other in the community since the late 1970s. Given that Dean’s parents proudly endorsed the union, I presumed Dean and Sam’s relationship was common knowledge, and therefore known to my dad. After all, it was on Facebook. But I never brought up Dean’s very public display with him.

Dad never spoke to Dean’s father, Ang, about it either. But when Ang read my same-sex marriage story in 2017, he contacted my dad.

‘I emailed Narong straight away,’ Ang said to me later. ‘I told him, “You should be proud of your son. It’s a very good article.”’

I was curious about why the pair had never spoken about their sons being gay. So, over crispy noodles, fried rice and Chinese tea, I sought answers from them at the restaurant near Chaddy. Ang wore a blue cap and a brown zip-up vest, and he giggled like a baby hyena. Dad sat opposite in his black beret.

‘We never talked about our children doing this or doing that,’ Ang said. ‘That doesn’t really interest me.’

‘So what did you talk about?’ I asked.

‘Politics,’ he said with his mouth full.

‘Which politics? Australian?’

‘Cambodian!’

In 2003, Ang had returned to Cambodia to serve as an opposition senator, leaving his family in Australia. He’d come back to Melbourne two years later, at the end of his term.

‘So Dean and I didn’t even rate a cursory mention: “How is your son going?”’

Ang shook his head and baby hyena-ed. ‘Being gay, it’s not significant. Sorry to say.’ He added, ‘I’m Buddhist, and Buddhism says nothing about gay people. It’s not a big issue. When Dean came out, I was okay. But my wife cried – she is a Catholic.’

For Dad, my sexuality was no longer a big issue. He relayed a story about a Christmas party he’d attended where a Cambodian woman suggested matchmaking me with her daughter. ‘I told her you were gay,’ Dad said proudly, ‘and she just shut up! She didn’t want to know any more. Like, full stop. She always wanted you and her daughter to match as a wife and husband.’

‘That’s the Cambodian thinking,’ Ang joined in. ‘But it’s not my thinking. Probably, I’m too white in my thinking.’ He giggled again. ‘Are you okay, both of you now? You should be proud.’

A long pause at the table. My eyes welled up, and I took a sip of white wine.

After I paid the bill, I drove Dad home while thinking our whole sixteen-year ordeal could have been avoided if he’d known about Dean years ago.

That night, my phone pinged. It was Dean on Facebook

Messenger. How was your dad tonight? Did they compare experiences?

I don’t know whether I have a story or not, I thumbed back. The premise was, here are these two Cambodian dads who never talked about their gay sons, yet when I asked them about it they said they never talked about their kids with each other full stop. They just talked about politics! WTF.

Face palm emoji from Dean. I find it odd that they never spoke to one another about it. Dads are weird.

Yes! I tried probing but they gave the same answer. Surely they would have said, you know, ‘How is your son?’; ‘Oh, he just had a civil union to a MAN’, etc.

He didn’t know about me before? Dean asked.

No.

If only we knew they had a purely politics-based relationship. I thought they both would’ve known? I would’ve definitely pushed for you to tell him if I had known he had difficulty accepting.