Looking back at the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, three decades on

By ALLISON HORE

April 10th marks the 30th anniversary of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. But in the three decades since the landmark Royal Commission, Indigenous activists say the core recommendations, of the report’s 339, have been enacted by any government.

The commission began in 1987 following campaigning by Indigenous activists over the death of 16-year-old John Peter Pat and a number of other Indigenous detainees.

Mr. Pat died in a Western Australia police cell in 1983. According to witnesses, arresting officers kicked Mr. Pat in the head and face, before dragging him into a van. When being removed from the van, witnesses say he was beaten and dropped onto the cement pathway.

He was taken into a cell and a little over an hour later, he was dead. Although witnesses claim neither Mr. Pat nor his fellow arrestees fought back, the officers involved pleaded self defence and their manslaughter charges were dropped.

On the 10th of April 1991, the commission returned with the findings of their inquiry and tabled a report with 339 recommendations.

Among the report’s recommendations were that imprisonment should only be used as a last resort, medical assistance must be called for detainees when necessary and every death in custody (Indigenous or otherwise) should be subject to “rigorous and accountable investigations.” The report also called for broader social changes including better cooperation with Indigenous communities and the initiation of a reconciliation process.

The commission’s legacy

Although the commission has been criticised as privileging legal perspectives over Indigenous voices and its limited scope, Elena Marchetti, Senior Lecturer at Griffith Law School, called the commission “the most comprehensive investigation ever undertaken into the deep disadvantage experienced by Indigenous people as a result of colonisation.”

But what has changed in the three decades since the report came in?

A global human rights report by Amnesty International highlighted the incarceration rate of Indigenous people as one of Australia’s key human rights issues. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 29 percent of the country’s prison population despite representing only 3.3 percent of the total population.

Indigenous deaths in custody continue, with more than 450 Indigenous people dying at the hands of Australia’s criminal justice system since 1991.

Just last month, on March 5th, a 35-year-old Aboriginal man died in Sydney’s Long Bay jail hospital after being found unresponsive in his cell. The cause of the man’s death is yet to be determined by the coroner. Three days later a 44-year-old Indigenous woman died in Silverwater Women’s Correctional Centre in Sydney’s West.

The pair are among the five Indigenous people who died in police custody across Australia in March.

And incarcerations are going up. A 2018 review by Deloitte commissioned by then Indigenous Affairs Minister, Nigel Scullion, found the rate of imprisonment for Indigenous people had doubled since the commission’s report was handed down.

Deloitte also found cell safety checks were insufficient and monitoring of Indigenous deaths in custody had decreased in recent years. They called the quality of data collected by police in regards to these deaths “an ongoing issue.”

Gomeroi, Dunghutti and Biripi Woman Tameeka Tighe, said the recommendations passed down by the Royal Commission were “no longer enough,” and widespread radical reform was urgently needed.

“How is it that 30 years after the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody our people are still dying at higher rates within the prison system,”

“It is no longer enough to call for the recommendations to be implemented, the entire prison system must be defunded and abolished.”

A push for action

In NSW, an inquiry into the handling of Indigenous incarceration and deaths in custody is currently underway in the Upper House. During the hearings, the New South Wales police watchdog called for its powers to be expanded to include deaths in jails with a senior commissioner, Lea Drake, saying there is a severe “lack of trust” in how these deaths are currently investigated.

Speaking at a rally coinciding with the hearing was Leetona Dungay, whose son David Dungay Jr died in Sydney’s Long Bay Jail in 2015. Dungay Jr was held down by 6 correctional officers and injected with sedatives after he ate rice crackers in his cell.

He had been due to be released on parole just three weeks after the incident occurred.

“The NSW government refusing to lift its finger to hold anyone accountable for the black deaths in custody, it must stop,” Ms. Dungay said.

“The system of police investigations for prison guards must stop. The police arrest of our aboriginal adults and children must stop.”

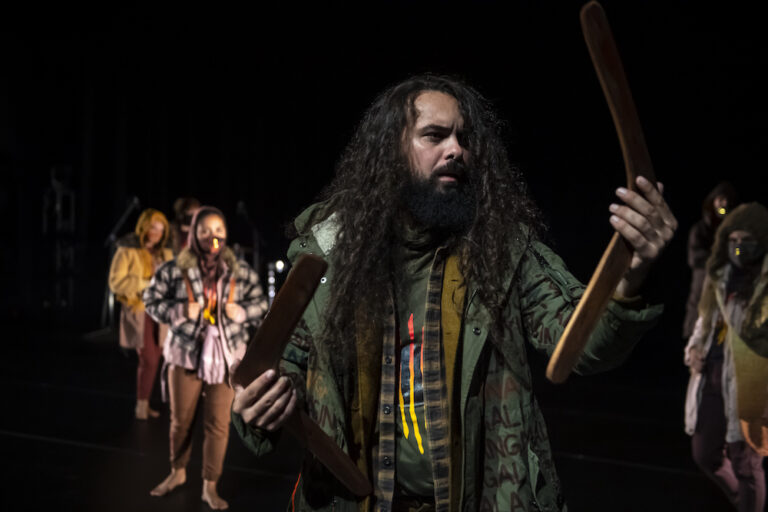

To mark 30 years since the Royal Commission, rallies will be happening across Australia calling for an end to black deaths in custody and justice for those lives already lost.

In Sydney, the protest will begin outside Town Hall at 1pm. Organisers say a COVID-19 safe protocol will be in place.