Why a Basic Income Guarantee makes economic sense

Opinion by MERRILL WITT

In a March research note to clients Macquarie Bank posed the following question: ‘Will COVID-19 redefine societies and economic models and inflict a prolonged and massive damage; or will it simply nudge us towards different policies (e.g. basic income guarantees & MMT) but still leave the essence of our societies intact, and the impact while deep, will not cause an economic reset?’

The fact that arguably Australia’s most influential investment bank referred to a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) as preferred economic policy options is noteworthy.

In conservative circles, a BIG is typically derided as a disincentive to work and MMT is derogatorily described as a “magical money tree” instead of a sensible economic tool for reviving our ailing economy.

A Basic Income Guarantee is gaining mainstream acceptance

Ironically, the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has done the world a favour by bringing into sharp relief the chronic problem of rising income and wealth inequality.

The risks these glaring inequities are posing to the post-pandemic economic recovery are forcing even hard-headed business people, economists and some governments to challenge long-held assumptions about what the government should do to ensure financial security for its citizens.

In Scotland, for example, a government established steering group recently published a detailed feasibility report endorsing a three year pilot study of a Universal Basic Income (UBI).

The scheme has already received the backing of the First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, who told the Guardian in May that the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus pandemic on middle and working class people made her think the “time has come” to consider a UBI.

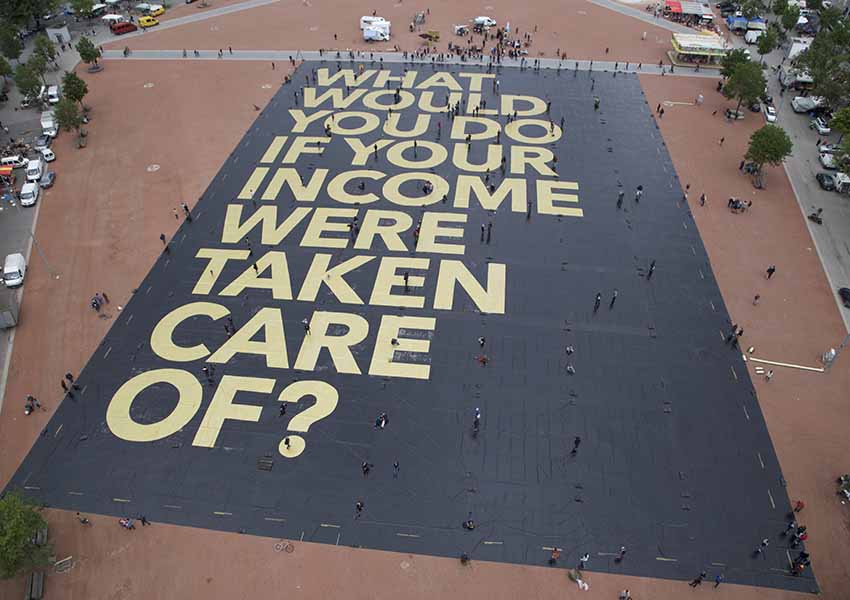

A UBI or BIG would see the government provide every adult with a steady source of income regardless of their employment situation. Depending on the design, it may or may not be means-tested and could replace all existing governmental assistance programs or complement them, as a wider safety net.

Sluggish wage growth and the casualisation of the Australian workforce have led to calls for a living wage

In Australia, the financial predicament of many of our citizens is not that dissimilar to Scotland’s. In the lead up to last year’s federal election, former Opposition Leader Bill Shorten argued that the minimum wage should be replaced by a living wage in order to address years of sluggish wage growth, which has not kept pace with increases in executive compensation and company profits.

More recently, revelations of “wage theft” by a number of high profile organisations across a range of industries have highlighted insecure working conditions and low pay. Just last week, The University of Melbourne agreed to repay around 1,500 academic casual staff in four faculties millions of dollars in underpaid wages.

What’s particularly distressing about the Melbourne University example is that it illustrates how higher education qualifications and skills training offer no protection against the increasing casualisation of the Australian workforce.

A Basic Income Guarantee will have a stimulatory effect on the economy

More than likely, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) would welcome the introduction of a government sponsored BIG to soften the detrimental impact of low-income growth on the prospects for a post COVID-19 economic recovery.

In a recent research note, the RBA cautioned that households might “permanently adjust their spending” if they don’t anticipate wages rising soon. Restrained spending patterns, it argues, will in turn discourage businesses from investing in labour or capital and consequently “damage the economy’s productive potential.”

Indeed, the introduction of the JobKeeper program and the $550 fortnightly supplement to the JobSeeker unemployment benefit have been economic lifelines for millions of Australians during the coronavirus pandemic.

Diana Mousina, a senior economist at AMP Capital, told the Nikkei Asian Review that “If we didn’t have these support measures, we would fall into an economic depression,” and The Grattan Institute’s Brendon Wood believes the reduction in JobSeeker to $250 a fortnight at the end of September will leave a “glaring hole in the economy.”

The corporate sector and the wealthy have been big beneficiaries of government largesse

In his book, Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn, Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes argues that tech companies like Facebook owe at least part of their success to a long-term pattern of government largesse towards the corporate sector.

Economic reforms like financial deregulation, tax cuts, lower trade tariffs and the privatisation of government services have helped global giants to amass huge capital and profits.

But this wealth transfer to corporations and their ultra-wealthy owners – “people like me,” says Hughes – has come at the expense of ordinary workers. Not only have jobs been lost to automation and low wage countries, but the cost of essentials like health, housing and education have escalated at the same time that access to government support has been tightened because of declining tax revenues.

Hughes’s observations are backed up by recent research from the World Bank. It found that in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) group of wealthy nations, the bottom 40 percent is estimated to own only 3 percent of household wealth (in contrast to 20 percent of income), while the top decile owns 50 percent of such wealth (25 percent of income).

This important research also highlights how poorer people have trouble accumulating wealth because they spend almost all of their income. Consequently, income support for low wage workers will likely flow straight back into the economy and spur economic growth.

Research by Deloitte Access Economics confirms the economic benefits of even a modest rise in unemployment benefits. Modelling in 2018 of a $75 a week increase in the former Newstart allowance showed that the rise “would have a range of ‘prosperity effects’, boosting the size of the economy and the number of people employed in Australia.” Deloitte estimated that “the latter effect would result in an additional 12,000 people being in work in 2020-21, though those effects would then fade over time.”

Modern Monetary Theory makes a Basic Income Guarantee an affordable proposal

Hughes believes a UBI should be funded by increasing taxes on the wealthy. But given that raising taxes in Australia, even on the rich, is a politically unpalatable option for our current conservative government, could the federal government find another way to fund a UBI? Here’s where MMT comes into play.

MMT contends that the size of a country’s debt and deficits is a political, not an economic consideration. In an interview with the Eureka Report’s Alan Kohler, Bill Mitchell, emeritus professor of economics at the University of Newcastle and one of the founders of MMT, said that “a sovereign country that issues its own currency has no financial constraints on what it spends.”

Inflation is the only real risk of more government spending, but it’s only a problem if supply constraints mean the increase in demand can’t be met without putting pressure of prices. That’s hardly a worry at the moment because the economy has lots of excess capacity due to high levels of unemployment and rising business inventories.

A recent Deloitte Economics Access report also dismissed concerns about increasing government debt. It labelled the “belief we have to pay off all this new debt” a “phantom menace” because debt will shrink relative to the size of the economy if growth returns.

Macquarie Bank’s recommendation that both a BIG and MMT should be considered to avoid inflicting “prolonged and massive damage” on the economy seems like very sound advice indeed. Not only would such an approach go a long way to curing Australia’s economic malaise, but it would help to address issues of fairness and equity, making for a more prosperous and cohesive society.