BY ALEC SMART

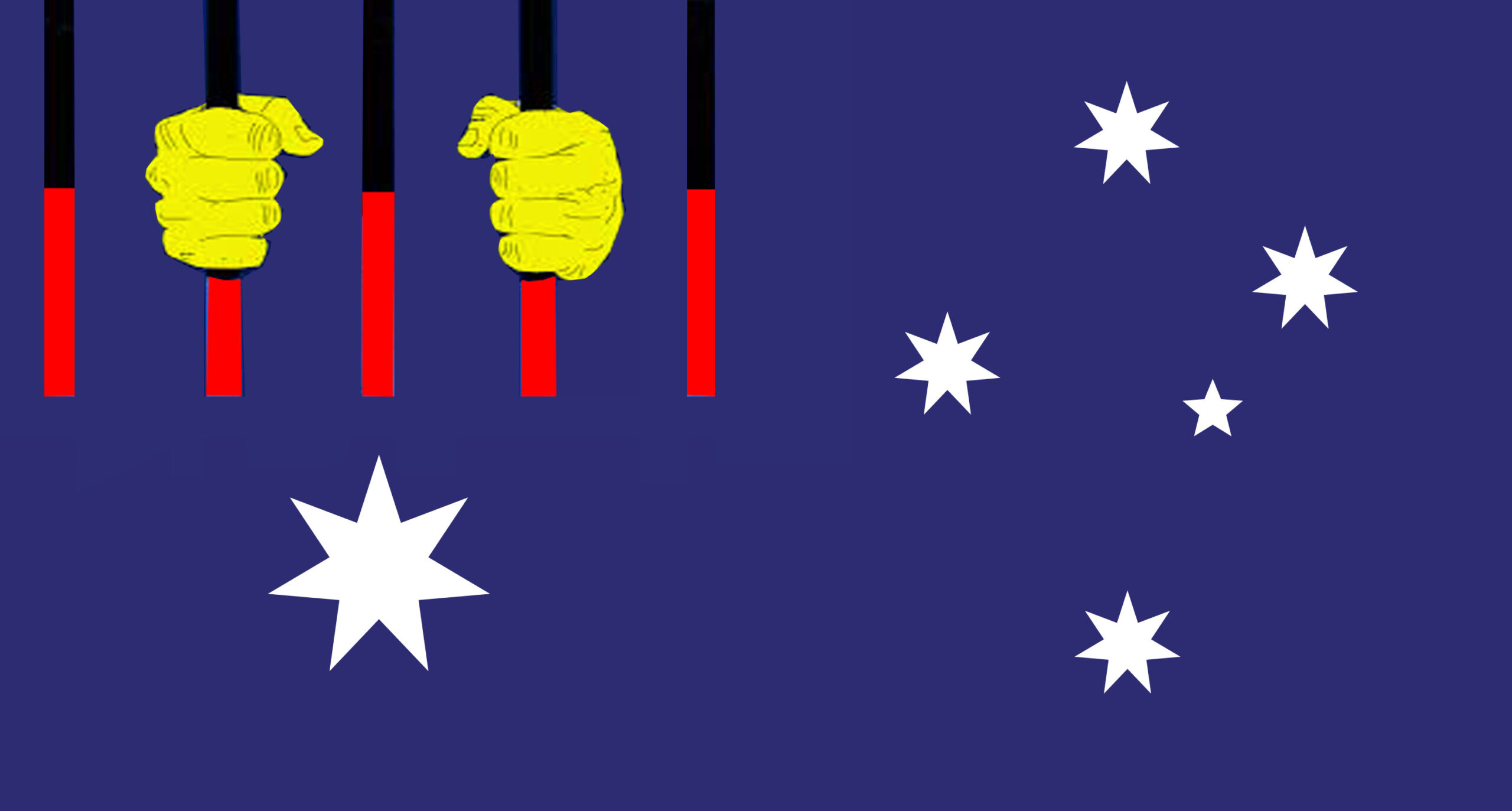

This Friday, September 15, a silent march is planned in Sydney to protest against Aboriginal deaths in custody. Organised by Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA), the march is intended to publicise the disturbingly high number of Aborigines dying in police custody or prisons.

According to the 2016 Australian Census, only 2.8% of the general population are Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, yet they account for 28% of the estimated 40,600 prisoners currently incarcerated.

In Western Australia, Aboriginals are incarcerated at nine times the rate black people were under the racist Apartheid regime in South Africa.

Tragically, Aborigines make up a larger percentage of those who die behind bars, particularly in the Northern Territory, which has the highest rate of Indigenous deaths in custody in Australia.

Between 1979 and 2011, there were 32 deaths in custody in the Northern Territory, 24 of which were Indigenous people. Northern Territory has the highest incarceration rate of Indigenous people in Australia, with 97 per cent of juvenile detainees and 82% of adult detainees.

ISJA spokesperson Raul Bassi explained the purpose of the rally.

“We intend to march with posters showing photos of 14 Aboriginal people who died in custody, including John Pat, Eric Whittaker, Eddie Murray, Ms. Julieka Dhu, Mulrunji Doomadgee and others.

“The posters feature their age, family details, and a description of the circumstances of their death.

“The march will go in circles and remain silent, like the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina.”

Founded in April 1977, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Spanish: Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo) is an association of mothers who met while trying to find the whereabouts of their children during the brutal military junta that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983.

Dismissed as Las Locas (‘mad women’) by the regime, they carried photos of their missing children and walked in circles around Plaza de Mayo in front of Casa Rosada presidential palace in Buenos Aires – silent, because public opposition to the military dictatorship was forbidden.

“We plan to do a silent march every three or four weeks,” Raul continued. “The first one will be at Pitt Street Mall at 5.30pm on 15th of September.”

The first Aboriginal death in custody was arguably Arabanoo, a native of the Eora nation from the area known as Manly, who was forcibly abducted by soldiers of the First Fleet on 31 December 1788.

He was captured on instructions of the first Governor, Arthur Philip, in order to facilitate communication between the natives and the British, and locked overnight in a hut in manacles and chains. He was a slow learner of English, and ultimately of little help to the settlers, who fared considerably better with his successor, Bennelong.

After only five months confinement among the invaders, Arabanoo succumbed to a smallpox outbreak on 18 May 1789 that killed an estimated 2000 indigenous people around Port Jackson.

Aboriginal deaths in custody went largely unrecorded and ignored over the following 200 years. It wasn’t until a series of protests throughout the 1980s after several highly publicised deaths of Aborigines in police cells that the Australian Government felt compelled to investigate.

Three of these remain controversial today; their families still demanding justice.

*Edward Murray – a 21-year-old rugby player arrested for being intoxicated and later found hanging in a police cell in the NSW town of Wee Waa on 12 June 1981.

*John Pat – a 16-year-old boy severely injured in a fight with four off-duty police officers who kicked him in the head and face outside Roebourne Hotel in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. He was arrested and taken unconscious to the juvenile lockup, where, on 28 September 1983, he died of his head injuries.

*Lloyd Boney – a 28-year-old rural labourer and troubled character in Brewarrina, NSW, who was arrested by police on 6 August 1987 for breach of bail conditions. He was found hanging by a football sock in the police cell merely 95 minutes after he was incarcerated.

The latter case was regarded as the catalyst for the federal government of Bob Hawke announcing a Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in October 1987. The Commission, held between 1987 and 1991, initially set out to examine 44 specific cases but eventually grew to 99, although it was limited to only investigate Indigenous deaths over a nine-year period between 1 January 1980 and 31 May 1989.

The 99 custodial deaths under its scrutiny consisted of 32 in Western Australia, 21 in South Australia and the Northern Territory, 27 in Queensland, and 19 across the southeastern states of NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.

In its final report, released April 1991 and costing over $40 million, the Commission ruled against finding any police and custodial officers responsible for violence against the victims, attributing suspicious deaths to ‘disease’, ‘self-inflicted hangings’, ‘external trauma, especially head injuries’ and ‘dangerous alcohol and other drug use.’

Nevertheless, it recorded ‘Glaring deficiencies existed in the standard of care afforded to many of the deceased,’ and made 339 recommendations, including:

*Police and prison officers should seek medical attention immediately if any doubt arises as to a detainee’s condition.

*Arrest people only when no other way exists for dealing with a problem.

*Initiate a formal process of reconciliation between Aboriginal people and the wider community (which led to the establishment of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation).

At the time of the Royal Commission’s final report in April 1991, Aboriginal people were eight times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Aboriginal people. A decade later that figure increased to 10 times more likely. An Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) study in 2013 found that between 2009 and 2013, the Aboriginal rate of incarceration soared 11 times faster than the non-Aboriginal rate.

Now they are 13 times more likely.

The number of Indigenous Australians to have died in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission is approaching 400.

The first silent march will be at Pitt Street Mall from 5.30pm on Friday September 15