Titus Andronicus

By Rita Bratovich.

Titus Andronicus was Shakespeare’s first tragedy and it makes Game Of Thrones look like Sesame Street!

Written in line with the genre then known as “revenge plays” and vengeful it is aplenty; by the end, the death toll is 14 alongside incidents of rape, mutilation, torture, and cannibalism. Oh, and also, most of this occurs among blood relatives. Obviously, there are some hard choices to be made when staging such a play, especially around how literally to depict the carnage. During an infamous, rather graphic performance at London’s Globe Theatre in 2014, audience members reportedly vomited and fainted. Thankfully, Bell Shakespeare’s upcoming staging at the Sydney Opera House will be more implicit than sanguinary.

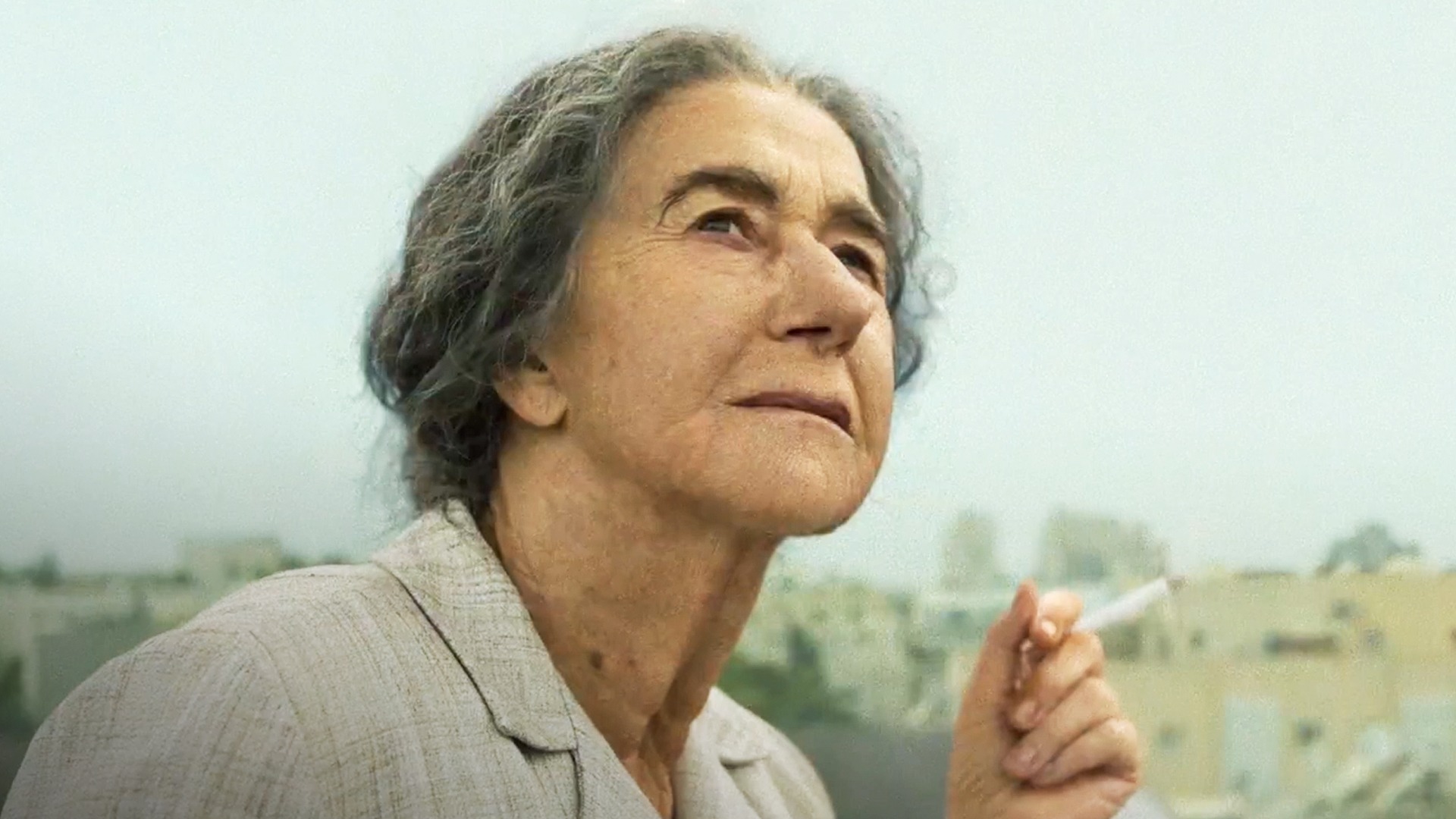

“This production is not about the gratuitousness of the violence; it’s about the toxicity of revenge, and also trying to bring together a sense of the humanity of the characters who do appalling things,” explains Jane Montgomery Griffiths who has been cast in the lead role of Titus. “It weaves together violence and families in a very interesting way.”

The play itself was written during a time when watching humans be dismembered was considered entertainment, so its extreme violence was pretty much de rigueur. However, that shouldn’t lead to an oversimplified reading of it.

“It’s not just black and white in this play, there are a fair few nuances,” says Griffiths. She says the director, Adena Jacobs, whom she describes as a visionary, is looking beyond the sensationalism of the violence. “Adena is trying to create something which actually finds beauty in the horror.”

When Griffiths was first informed that she had been cast as Titus – who remains a male character – she thought about visiting the Melbourne barracks and learning how to be a drill sergeant or soldier.

“Then as we got into rehearsal, that became less and less significant because, I suppose, one of the things now that we are as a society is we’re much more open to non-binary gender positions, we’re allowed to play, and I found the idea of playing with the masculine and the feminine really interesting,” says Griffiths.

Adding another dimension is the fact that she is a mother. She found she had to coalesce her maternal instinct with her perception of the male psyche. In one scene, Titus kills his own son in a fit of rage.

“As a mother, I couldn’t imagine doing that; as a twisted war veteran, which is what Titus is, I can imagine him doing that,” says Griffiths.

With its near relentless parade of bloodletting, it might seem like the play is thin on character development, but Griffiths emphatically disputes that idea.

“For Titus, there’s an incredible journey. I’ve played some pretty meaty roles, but this is without a doubt the biggest journey of a character I’ve ever experienced.”

It’s a journey that takes Griffiths into some disturbing territory, but she finds it energising, strangely beautiful, even cathartic.

“Actors are funny people …and virtually all actors not just love a challenge, but love having a role where they can go into places and into emotions that they would hopefully never experience in their life,” she explains. “Certainly for me, exploring those immense emotions is fascinating, and sometimes very satisfying. You know it’s like when you have a really good cry to get it out of your system and you feel better after that.”

Does she feel apprehensive about what she might find?

“Nah. I’ve done too many dark roles for that. I think I’ve discovered all the strangeness in myself by now.”

Whatever that strangeness is clearly has a strong appeal for director Adena Jacobs. She has worked with Griffiths on several projects during the last ten years and she thought exclusively of her for the role of Titus. Similarly, she has cast Tariro Mavondo in the male role of Aaron, the Moor. The characters are still addressed as male but there is no attempt to hide the fact they are being played by women. Other characters are played by an ensemble in multiple roles. Jacobs says it gives the play fluidity and makes it less conventional. As written, it is predominantly male with only two female characters.

“That kind of arrangement is [ …] very uninteresting to us now, and problematic – it leaves us nowhere to go except just to say that there’s a lot of patriarchal violence – things we know,” says Jacobs. “We are a group of artists in 2019 and we’re primarily a group of queer and feminist artists, so our relationship to these particular images of violence and these questions and ideas are very different.”

Switching genders reframes the play, provides an alternative perspective. For instance, there is a scene at the end of the play where Titus kills his daughter for shame, and the idea of a male general killing his daughter for shame has a different meaning to Jane as Titus and as a woman doing it. Ultimately, the play is not so much about gender as it is about family, violence, and retribution.

“The emotional core of the piece is all of these parents’ relationship with their children and their desperate desire to keep their children safe – which they fail at and which leads to dire consequences and vengeful acts…” says Jacobs. She sees the intergenerational and perpetual violence as one of its overarching themes. “These cycles of violence are reiterated through the generations and they will continue to be reiterated. There is something so fatalistic and nihilistic about the text as written.”

In terms of staging, Jacobs has created a surreal landscape that is neither modern nor historical.

“It feels like a newly made-up world in some way, it’s a parallel world,” she explains. The costumes are also non-definitive, non-temporal, non-gendered. The design overall reflects on the history, myth, and art around violence.

“It’s a mythological space, so it kind of draws from all those things.”

The violence is implicit, not graphic, but very much at front and centre thematically.

“I think Shakespeare’s intention was to interrogate violence, and why there is such a scale of violence and what our relationship is to it, you know once we’re surrounded by it and affected by it to the point of excess.”

Aug 27-Sep 27. Sydney Opera House, Bennelong Point, Sydney. $45-$95+b.f. Tickets & Info: www.bellshakespeare.com.au

CONTENT WARNING

Titus Andronicus contains rape, body harm, amputation, murder, infanticide, gendered and racialised violence. Please be advised that this production will include this confronting content. It is recommended that any audience member concerned about this subject matter should familiarise themselves with the play before purchasing tickets.