On Return and What Remains

It is not only wounded soldiers who bear the scars of war. A new exhibition at Artspace contemplates the broader casualties of war, from displaced civilians to traumatised military personnel, and the broken communities to which they return.

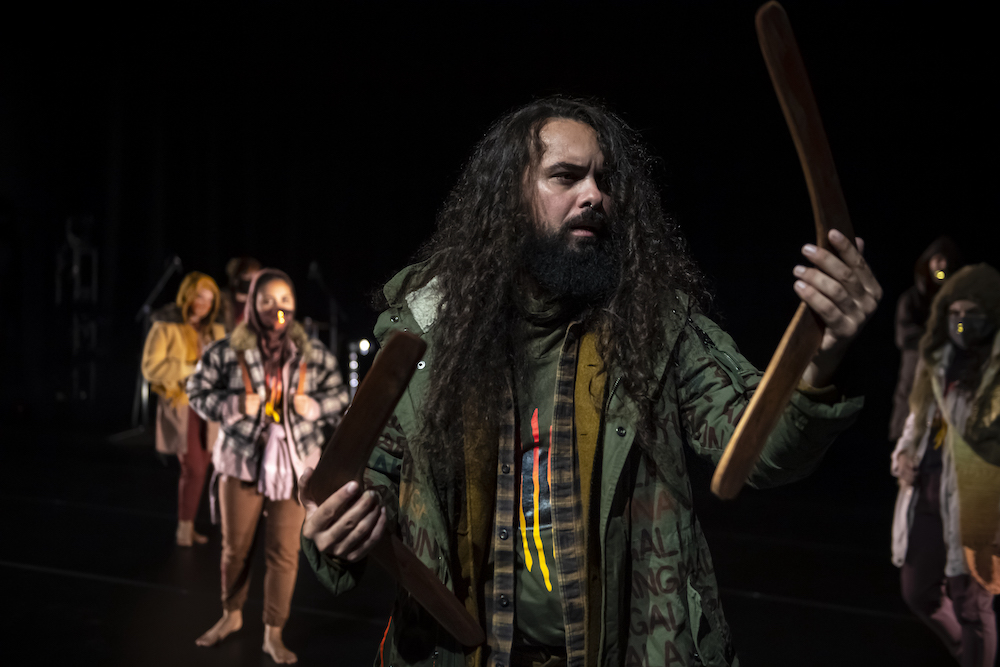

On Return and What Remains is a group exhibition focused on the challenges endured by those who serve on the frontlines of global conflicts, and those whose lives are irrevocably altered by war. The project includes work from artists Khadim Ali, Bonita Ely, Baden Pailthorpe and Richard Mosse among others.

War is an unending pattern that stains humanity’s collective narrative. No sooner has the world turned the page on Afghanistan than Prime Minister Abbott announces that Australian troops may be sent back to Iraq.

Curator Mark Feary says, “Beyond the mythology of war – the rhetoric of valour, honour, glory and defence of nationhood – we need to question the real price that is paid, individually and collectively. This exhibition unravels some of the personal narratives behind the official story of war, to look at the individual sacrifices that are made – not just on the battlefield, but once the conflict has ended.”

The exhibition explores the predicaments faced by military personnel who return home and try to integrate back into civilian life.

Mr Feary says, “We send troops to far-off lands, to fight against people and value systems that are removed from our own world and reality, and may have very little relationship to our own values or politics.

“When the troops return home, so far from the point of conflict, and life appears to be completely unchanged and unimpacted [sic], what remains? What remains physically and psychologically, of that time, of that conflict, and what has been lost?”

Artist Bonita Ely is the daughter of a WWII veteran who grew up in Robinvale, a soldier settlement town near Mildura.

Ms Ely says, “Many of the returned soldiers in Robinvale were grappling with untreated Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). My father came home from war a changed man; he became aggressive, irrational, and hyper-vigilant – everything had to be just so.

“The RSL offered the returned servicemen a sense of camaraderie and a space where they could get together to relax, relate and escape with heavy drinking. But the families often bore the brunt of the untreated PTSD and consequent aggressive or militant behaviour.”

Ms Ely has refashioned domestic furniture into two military-themed sculptures – a watchtower and a machine gun. Made from a vintage Singer sewing machine, Ms Ely’s Sewing Machine Gun symbolises women’s industry during wartime.

Ms Ely says, “The Singer was a symbol of womanhood in the war era – everybody had one. My mother was an accomplished dressmaker – she made all of our clothes. There is a significant dichotomy between the sewing machine and the machine gun – one is a feminine and practical tool, the other is so destructively masculine.”

Mr Feary says, “Bonita’s work is informed by the personal impact of her shell-shocked father’s return from World War II. She reflects on the domestication of post-war trauma – the ripple effect of untreated trauma.

“We hear so much political discussion about bringing back the troops – the return of the soldiers is often regarded as the end-game objective of participation in war. But we must also think more deeply about how we can support those troops when they come home,” he adds.

The true toll of war extends far beyond the deaths incurred in the warzone. A thorough survey of collateral damage must also recognise the suffering of refugees forced to flee their homelands.

Hazara artist Khadim Ali grew up in Quetta, a Pakistani town on the Afghan border. The Hazara people are a Shia ethnic group who, for generations, have endured political, social and economic persecution, and denial of basic civil rights.

Mr Ali’s trajectory as an artist has been shaped by war. The Taliban and al-Qaeda regimes have carried out genocides on the Hazara population.

Mr Ali says, “In Afghanistan and in Pakistan, Hazaras are considered infidels. We are demonised, dehumanised and displaced; displaced from our heartland, displaced from the status of humanity.”

Leaving family behind, Mr Ali fled war-ravaged Afghanistan to pursue a better life in Australia. In 2011, a suicide bomber destroyed his parents’ home in Pakistan.

He says, “When the house collapsed, all of my paintings and artworks were destroyed. I lost everything. The only thing that I could see in the rubble was our red carpets. Afghan rugs are durable – they were the only things that survived the blast.”

From that moment Ali started to incorporate rug making into his artwork. His new work Transition questions the 2014 evacuation of troops from Afghanistan. It features an intricate painting emblazoned on a sturdy traditional Afghan rug.

Mr Ali ponders, “What do we achieve with war? When the Australian troops went to Afghanistan, I hoped that my homeland would be freed and the Hazara people would be able to live without persecution. But the troops have left Afghanistan and the Taliban is still there. The dream is broken. Was it all for nothing? Just to become a demon fighting another demon?” (CC)

Until Oct 12, Artspace, The Gunnery, 43–51 Cowper Wharf Roadway, Woolloomooloo, free, artspace.org.au